A seemingly never-ending stream of Italian prisoners pouring over a bridge following the capture of Bardia during the British sweep west through Libya, which was climaxed by the capture of Benghazi. In all, the British captured 100,000 Italians, it was claimed.

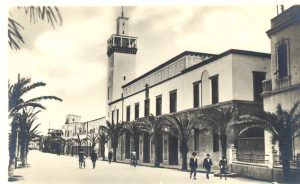

It was a hot Sunday in 1955, and 9-year-old Giovanni Chichiriccò headed to the beach in Tripoli to enjoy the gorgeous blue sea and baby-powder-fine sand with his family, as he did every weekend. There he played with his Libyan friends, practiced the local Arabic dialect, splashed in the clear water and ran wild on the dunes. “At the beginning, my parents came with me,” he says, but as he grew older, they let him go by himself, “and it was real party time.” For lunch, they had a mix of Italian and Libyan cuisine, and sometimes American hamburgers — the latest foodie craze spread locally by American troops after World War II. In the evenings, he often went to the theater to see Italian actors and signers perform in ancient Roman sites.

Today, at 71, Chichiriccò looks back with melancholy at those great days and at his “lost Libya, a piece of my heart.” He was forced to leave his childhood home behind when his family was kicked out of Libya in 1970, following Muammar Gaddafi’s rise to power. He was in his late 20s at the time, a young Italian man working as a technician at the Libyan bank for rural funds.

Each time I visited, it looked like a ghost town packed with my childhood memories.

Giovanni Chichiriccò

“Libya was our El Dorado,” he says, noting how it had everything they needed to live well, from an “abundance of food and fresh fruit to the lively locales where Italians, Libyans and Jews rubbed shoulders together, fully integrated.” The deep blue color of Libya’s sea remains a part of his soul. In Tripoli he had the privilege of tasting hamburgers long before they reached Italy. His father had contributed to building the country’s first Western-style theaters and cinemas, where iconic Italian actors like Vittorio Gassman and beauty queens like Gina Lollobrigida took to the stage.

Chichiriccò was born in Tripoli, as were his parents. His grandparents were among the hundreds of thousands of Italian settlers who started migrating to Libya after 1911, when Italy defeated Turkey and founded the Tripolitania colony — Libya’s former Italian name. They were artisans, bakers, woodcutters, builders, technicians and farmers who longed for a fresh start in a new land, even if covered by a desert (which they largely rejuvenated for agricultural use and animal breeding).

When Gaddafi forced them to repatriate, putting an end to their pleasant expat life, all their properties, businesses, farms and bank accounts were seized. They were forbidden to return to Libya, and in Italy, where they had no homes, they were forced to live in refugee camps and felt like foreigners in their own country.

Decades have passed, but the wound remains raw. Ever since their forced exile, they’ve been battling to be granted more monetary compensation from the Italian government — which had sent their families to Libya in the first place — for what they lost. They have even founded a lobby to defend their interests, uniting 20,000 descendants of former settlers.

In 2009, Premier Silvio Berlusconi and Gaddafi made a deal enabling some of the nostalgic former settlers a chance to return to their former homes, at least for a holiday. But “each time I visited, it looked like a ghost town packed with my childhood memories,” says Chichiriccò, noting how much his old house had changed. “I didn’t have the courage to knock and see who was now living there.”

The battle for full compensation remains a stalemate. “We had asked for 350 million euros, which is only 10 percent of the total value of what we were deprived of in terms of richness and properties,” explains Daniele Lombardi, communications director of the Italians Repatriated From Libya Association. “So far, Italy’s state has granted us only 200 million euros, and we have no idea when the remaining part will be paid.”

Most frustrating for the returnees was the lack of support. The government was more interested in striking important commercial deals — mainly oil and infrastructure investments — with Libyan authorities than in reclaiming the lost goods, according to Arturo Varvelli, researcher at Milan’s Institute for International Political Studies (ISPI) global affairs think tank. Varvelli was the first Italian researcher allowed to study the archives of Italy’s Foreign Ministry: “It came up that all along these decades of tense bilateral ties, the government adopted a strategy of ‘parallel economic compensation,’ preferring to pursue its own commercial interests rather than those of the repatriated Italians,” says Varvelli, who has published a book on these controversial papers.

The “soft” approach of Berlusconi toward Gaddafi culminated in an absurd “love affair” between the two, with an extravagantly wild institutional party in Rome in 2010 to honor Gaddafi. It featured Libyan horses, belly dancers and warrior performances, and Gaddafi was granted the privilege of sleeping in a luxury Bedouin tent in a public park. Berlusconi was even seen kissing Gaddafi’s hand after oil deals were struck — a friendship that came to an abrupt end with Gaddafi’s downfall and death a year later.

“Since then, given the political unrest Libya faces, I haven’t returned,” says Chichiriccò. But during his visits in 2009 and 2010, he felt like he was returning home. After just a few days, he had picked back up his childhood tongue, met with old friends and was chatting with locals who were happy to hear an Italian speak their language. Now he can only dream of peace for the Libyan people … and of flying back to Tripoli as soon as possible.